First published in Dutch on the 10th of May 2010

A curious phenomenon

My question stems from a phenomenon which I often encounter. A student may tell me they comprehend an opinion, advice, or strategy only to be unable to apply it in their studies: “I get how I should plan my work, but I fail to stick to the schedule,” or “I understand the methods of reading strategically, but I find it hard to skip over sentences,” or “I know it is stupid to think that I will get a low grade, but I cannot help it.”

What do the different forms of comprehension mean if it is not helpful to these people? Their complaints would be logical if they comprehend “it” but simultaneously reject it as invalid or not applicable to their specific situation. This is a common and legitimate reaction. Sometimes the rejection is explicit: “I understand what you are saying, but I do not believe it.” And sometimes it is implicit when people use the familiar phrase, “yes, but…”

The students in my examples, however, do accept the advice and techniques as valid; they confirm that they understand the information and express the willingness to put it in practice. Nevertheless, they fail to do so despite their comprehension and acceptance of the material. This is very curious.

Different levels of comprehension

Apparently there are different levels of comprehension. In education, the taxonomy by Benjamin Bloom (Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, 1956) is often used to distinguish between these levels. His taxonomy has been normative for decades in describing the development in cognitive comprehension.

Cognitive Comprehension(Bloom’s taxonomy)

| To know | Ability to remember and/or reproduce information |

| To comprehend | Ability to (re)organize information mentally |

| To apply | Ability to apply information in practical situations |

| To analyze | Ability to examine processes and identify cause and effect, rules and exceptions, etc. |

| To synthesize | Ability to formulate original and creative connections |

| To evaluate | Ability to valuate an idea, an application, or a solution |

Cognitive comprehension is insufficient

Bloom’s discussion is valuable but in practical situations it often proves to be insufficient when one needs to get a grip on certain persisting learning problems. The theory of planning, for instance, is relatively simple; it is by no means comparable to complex theory like Einstein’s theory of relativity. A student should, therefore, be able to grasp the different cognitive levels fairly quickly. Even so, I coach many students who are perfectly capable of going through all the steps towards the creation and execution of a plan and still find themselves unable to stick to it. They know the steps in theory. This distinction exposes the problem; all levels are theoretical in nature. Their complexity may increase with every level, but it does not have to result in the ability to apply the information in practical situation. The practical application does not automatically sprout from an ever deeper theoretical dissection and analysis of the material.

Comprehension is change

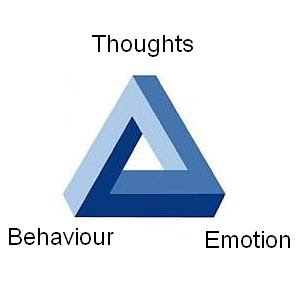

In a previous essay (Nothing is more practical than a good theory, October 2011) I wrote about study motivation and argued that learning equals change. Comprehension of new insights, then, is also a kind of change. It alters our experience. Experience is what we think (thoughts), what we do (behavior), and what we feel (emotion). These three components form an indissoluble unity.

Bloom’s taxonomy only applies to our thinking. It does not discuss emotion and behavior. The effect is that the journey through the cognitive levels of comprehension does not necessarily result in changes in experience when the other two components are left untouched.

Supplementary taxonomies

The limitations of the cognitive taxonomy were quickly recognized, which was followed by a supplementary taxonomy about emotion designed by David Krathwohl (Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook II: Affective Domain, 1964). I understand this taxonomy to be a discussion of the different levels of affective comprehension:

Affective Comprehension (Krathwohl’s Taxonomy)

| To receive | Conscious of the existence of certain ideas. |

| To respond | Acknowledging ideas with a (minimal) response. |

| To value | Willingness to recognize ideas as valuable. |

| To organize | Willingness to bring together ideas with existing personal thoughts and philosophies harmoniously. |

| To characterize | Person accepts ideas as part of personal value system. |

A third taxonomy completes the picture. Anita Harrow (A taxonomy of the Psychomotor Domain, 1972) focused on the three levels of psychomotoricity. She studies movement in particular, but I believe that her findings are useful in different areas of behavior as well. Her taxonomy, then, describes what I call levels of behavioral comprehension:

Behavioral Comprehension (Harrow’s Taxonomy)

| Reflex behaviour | Reaction to stimuli not consciously learned (e.g. body posture, tension in muscles) |

| Basis behaviour | Combinations of complex reflex movements (e.g. walking, running, sitting) |

| Perceptual behavior | Ability to adapt movements in favor of more complex achievements (e.g. jumping rope, catching or throwing a ball, writing and typing) |

| Physical activities | Physical achievements resulting from a degree of power, perseverance, precision, concentration, etc. (e.g. sports, taking notes) |

| Skilled behavior | Person is highly skilled (e.g. achieved a high level in sports or has the ability to make effective mindmaps) |

| Physical expression | Person has distinctive personal style |

The phenomenon becomes understandable

The supplementary taxonomies discussing emotion and behavior make my students’ problems understandable. A student may reach a high level of cognitive comprehension but simultaneously fall short in the areas of affective and behavioral comprehension. Which levels of comprehension are exposed in the phrase “I get how I should plan my work, but I fail to stick to the schedule” ?

Cognitive domain: in this domain the student has most likely reached the level of application, thinking that this is enough. However, in actuality it is insufficient because they are only able to work through the steps of the plan theoretically. Like I explained before, this is not the same as executing the plan in the student’s own practical situation. Bloom argued that analysis, synthesis, and evaluation are necessary levels to achieve the transfer; a student must master each of these levels to be able to translate the planning techniques to their personal circumstances. I believe that an affective and behavioral development is also needed to reach these levels of cognitive comprehension.

Affective domain: in this domain the student does not move beyond an appreciation of the techniques’ validity. They accept the validity of the techniques and award them merit. This, however, is far removed from the final two affective levels. The information needs to be connected to an existing personal perception (level 4) and internalized in such a way that they become an integral part of a student’s values (level 5).

Behavioral domain: the student seems to show particularly poor development in this domain. In my experience these students commonly fail to move beyond the second (or third) level. Following simple reflection they often construct a basic plan which does not fit their actual activities in any way. At even the slightest hurdle they stop applying reflection and immediately throw in the towel. The plan is not interpreted as a physical activity which requires perseverance, precision, and concentration (level 4). Let alone that it could become part of a personal style (level 5).

My proposition

My proposition is that high level “comprehension” has to be brought about cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally simultaneously. In order to comprehend something we need to be willing to change. It does not need to be an “extreme-makeover” type of change where we must radically break with past experiences. We do not even notice most changes because they are part of a natural and unconscious development. However radical or subtle the change may have to be, I believe it is impossible to truly comprehend something new cognitively without changes in the affective and behavioral domains. The conclusion is that the students mentioned above have not, in fact, understood it at all.

No Comments